Understanding OAuth 2.0

In today’s digital world, we often need to access various online services and platforms to perform different tasks, such as checking emails, shopping online, or streaming music. However, each of these services requires us to create and manage a separate account with a username and password. This can be cumbersome and insecure, as we may end up using weak or reused passwords, or forgetting them altogether.

Moreover, some of these services may want to access our data from other services, such as our contacts, photos, or location. For example, a travel app may want to access our calendar to suggest the best time for a trip, or a music app may want to access our social media to recommend songs based on our friends’ preferences. However, giving these services our credentials for other services is not a good idea, as it exposes us to the risk of data breaches and identity theft.

So how can we securely and conveniently authorize third-party applications to access our data without exposing our credentials? This is where OAuth 2.0 comes in.

OAuth 2.0 is a widely used protocol that enables applications to obtain limited access to user accounts on an HTTP service, such as Facebook, Google or Twitter. It works by delegating user authentication to the service that hosts the user account, and authorizing third-party applications to access the user account. OAuth 2.0 provides authorization flows for web and desktop applications, as well as mobile devices.

Understanding OAuth 2.0 is important for developers, businesses, and users alike. For developers, OAuth 2.0 simplifies the development of secure and user-friendly applications that can access various online services. For businesses, OAuth 2.0 enables them to offer their APIs to third-party developers and partners in a controlled and secure manner. For users, OAuth 2.0 gives them more control and transparency over their data and privacy.

In this blog post, we will explore the basics of OAuth 2.0, the authorization flow, the components and terminology, the common use cases and implementations, the best practices for security, and the comparison with OAuth 1.0a.

Understanding the Basics of OAuth

OAuth 2.0 is an authorization protocol that enables third-party applications to access user data without exposing credentials. The main purpose of OAuth 2.0 is to allow users to grant permission to applications to access their data on other services, such as Facebook, Google, or Twitter.

There are four key players in the OAuth 2.0 process:

- Resource Owner: The resource owner is the user who authorizes an application to access their account. The application’s access to the user’s account is limited to the scope of the authorization granted (e.g., read or write access).

- Client: The client is the application that wants to access the user’s account. Before it may do so, it must be authorized by the user, and the authorization must be validated by the API.

- Authorization Server: The authorization server verifies the identity of the user then issues access tokens to the application.

- Resource Server: The resource server hosts the protected user accounts.

From an application developer’s point of view, a service’s API fulfills both the resource and authorization server roles. We will refer to both of these roles combined as the Service or API role.

The high-level explanation of the authorization flow is as follows:

- The application requests authorization to access service resources from the user.

- If the user authorized the request, the application receives an authorization grant.

- The application requests an access token from the authorization server (API) by presenting authentication of its own identity and the authorization grant.

- If the application identity is authenticated and the authorization grant is valid, the authorization server (API) issues an access token to the application.

- The application requests the resource from the resource server (API) and presents the access token for authentication.

- If the access token is valid, the resource server (API) serves the resource to the application.

The actual flow of this process will differ depending on the authorization grant type in use, but this is the general idea. We will explore different grant types in the next section.

The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Flow

OAuth 2.0 defines four main grant types for obtaining an authorization grant from a resource owner:

- Authorization Code Grant: This is the most commonly used grant type for web applications that can securely store a client secret on their server-side.

- Implicit Grant: This is a simplified grant type for browser-based or mobile applications that cannot store a client secret securely.

- Resource Owner Password Credentials Grant: This is a grant type for trusted applications that can obtain the resource owner’s credentials directly.

- Client Credentials Grant: This is a grant type for applications that act on their own behalf rather than on behalf of a user.

Each grant type has its own steps and parameters, as well as advantages and disadvantages. Let’s look at each grant type in more detail, with diagrams and real-world use cases.

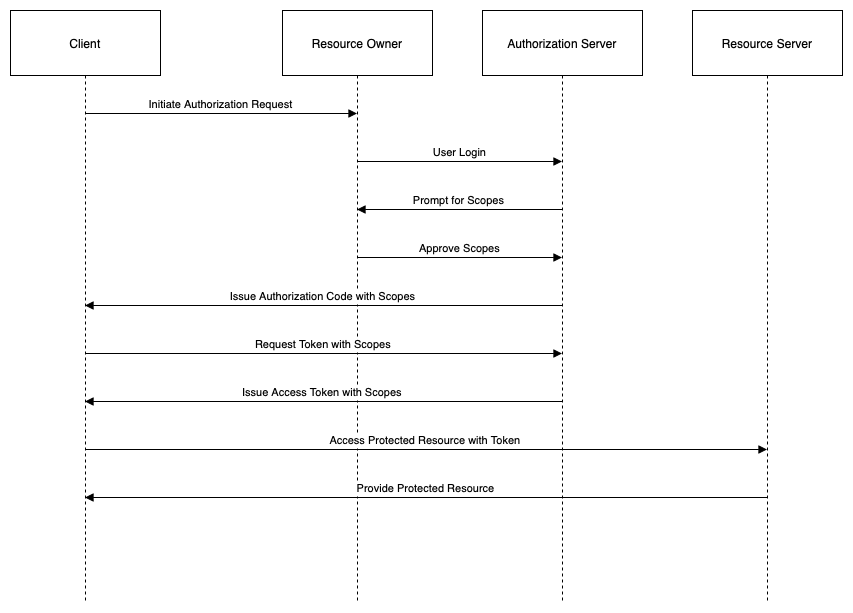

Authorization Code Grant

The authorization code grant is the most commonly used grant type for web applications that can securely store a client secret on their server-side. The client secret is a confidential piece of information that is used to authenticate the client to the authorization server. The authorization code grant provides a high level of security, as the access token is never exposed to the user agent (e.g., browser) or other intermediaries.

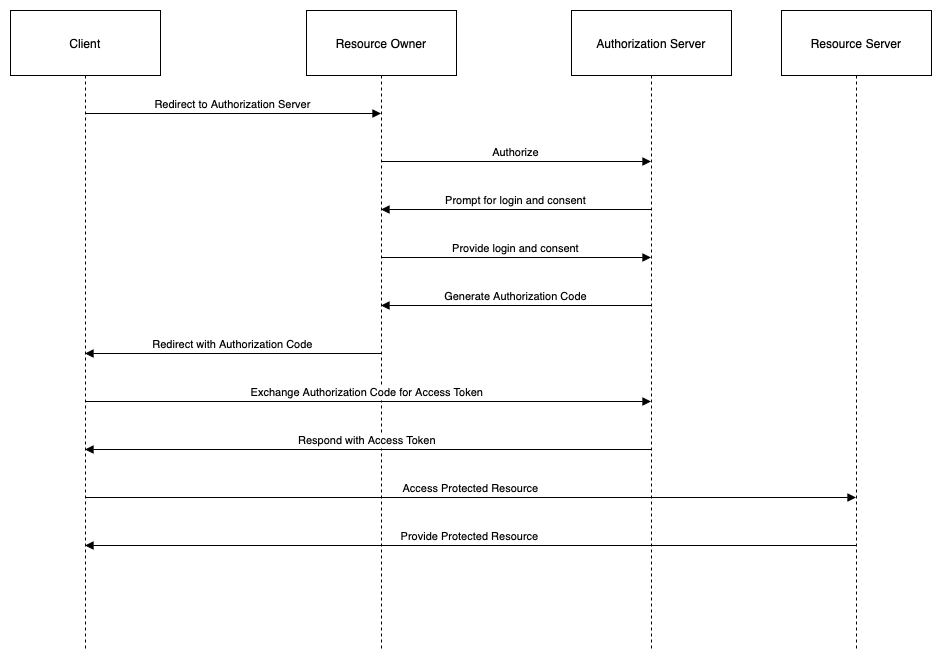

The steps of the authorization code grant are as follows:

- The client (application) initiates the flow by directing the resource owner (user) to the authorization endpoint (service) with a request for an authorization code. The request includes the client identifier, the requested scope, the redirection URI, and an optional state parameter.

- The authorization server authenticates the resource owner and obtains their consent for the requested scope. If successful, the authorization server redirects the resource owner back to the client with an authorization code and the state parameter (if present) in the query string.

- The client verifies the state parameter (if present) and requests an access token from the token endpoint (service) by presenting the authorization code, the client identifier, the client secret, and the redirection URI.

- The authorization server validates the authorization code, the client identity, and the redirection URI. If successful, the authorization server issues an access token (and optionally a refresh token) to the client.

- The client requests the protected resource from the resource server (service) by presenting the access token in the HTTP Authorization header or as a query parameter.

- The resource server validates the access token and serves the requested resource to the client.

The following diagram illustrates this flow:

A typical use case for this grant type is a web application that needs to access a user’s data on another service, such as Google Calendar or Spotify. For example, a travel app may want to access a user’s Google Calendar to suggest the best time for a trip, or a music app may want to access a user’s Spotify playlists to recommend songs based on their preferences.

Some of the advantages of this grant type are:

- It provides a high level of security, as the access token is never exposed to the user agent or other intermediaries.

- It supports refresh tokens, which can be used to obtain new access tokens without requiring user interaction.

- It allows for dynamic and flexible redirection URIs, which can be useful for applications that run on multiple domains or platforms.

Some of the disadvantages of this grant type are:

- It requires multiple requests and redirects, which can increase latency and complexity.

- It requires server-side logic and storage, which can increase development and maintenance costs.

- It may not work well for applications that run on devices with limited capabilities or network connectivity, such as smart TVs or IoT devices.

Implicit Grant

The implicit grant is a simplified grant type for browser-based or mobile applications that cannot store a client secret securely. The client secret is a confidential piece of information that is used to authenticate the client to the authorization server. The implicit grant does not require a client secret, as it relies on the user agent (e.g., browser) to receive and store the access token.

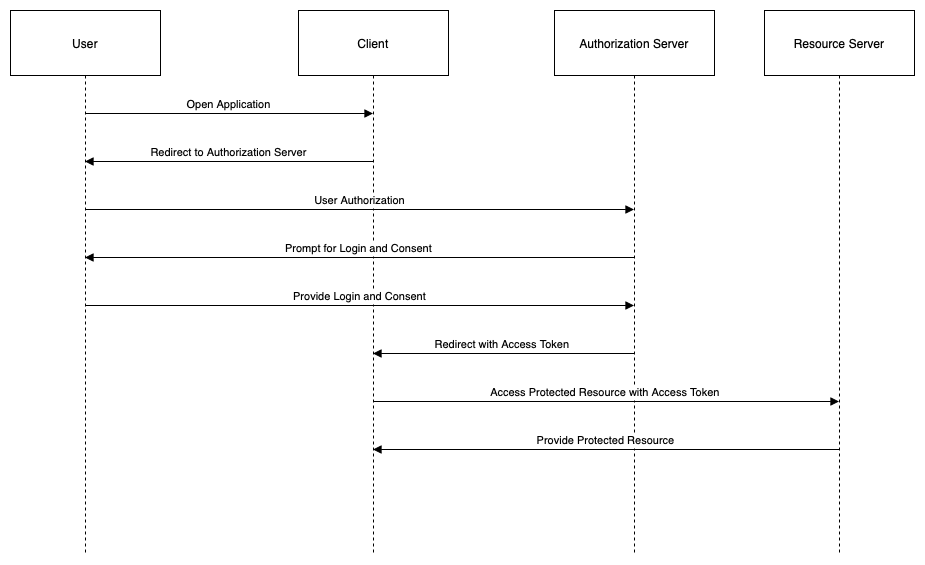

The steps of the implicit grant are as follows:

- The client (application) initiates the flow by directing the resource owner (user) to the authorization endpoint (service) with a request for an access token. The request includes the client identifier, the requested scope, the redirection URI, and an optional state parameter.

- The authorization server authenticates the resource owner and obtains their consent for the requested scope. If successful, the authorization server redirects the resource owner back to the client with an access token and the state parameter (if present) in the fragment part of the redirection URI.

- The user agent (browser) retains the fragment part of the redirection URI, which contains the access token, and does not send it to the web server hosting the client.

- The user agent (browser) passes the access token from the fragment part of the redirection URI to the client via scripting.

- The client requests the protected resource from the resource server (service) by presenting the access token in the HTTP Authorization header or as a query parameter.

- The resource server validates the access token and serves the requested resource to the client.

The following diagram illustrates this flow:

A typical use case for this grant type is a single-page application (SPA) that runs entirely in the browser and needs to access a user’s data on another service, such as Facebook or Twitter. For example, a social media app may want to access a user’s Facebook profile or Twitter timeline to display their posts or tweets.

Some of the advantages of this grant type are:

- It is simple and easy to implement, as it does not require server-side logic or storage.

- It provides immediate feedback to the user, as the access token is obtained in one request and redirect.

- It works well for applications that run on devices with limited capabilities or network connectivity, such as smart TVs or IoT devices.

Some of the disadvantages of this grant type are:

- It is less secure, as the access token is exposed to the user agent and other intermediaries, such as proxies or caches.

- It does not support refresh tokens, which means the user has to re-authenticate when the access token expires.

- It requires a fixed and registered redirection URI, which can limit the flexibility and scalability of the application.

Resource Owner Password Credentials Grant

The resource owner password credentials grant is a grant type for trusted applications that can obtain the resource owner’s credentials directly. The resource owner’s credentials are a pair of username and password that are used to authenticate the resource owner to the authorization server. The resource owner password credentials grant provides a simple and direct way for applications to access user data, but it comes with a high risk of compromising user security and privacy.

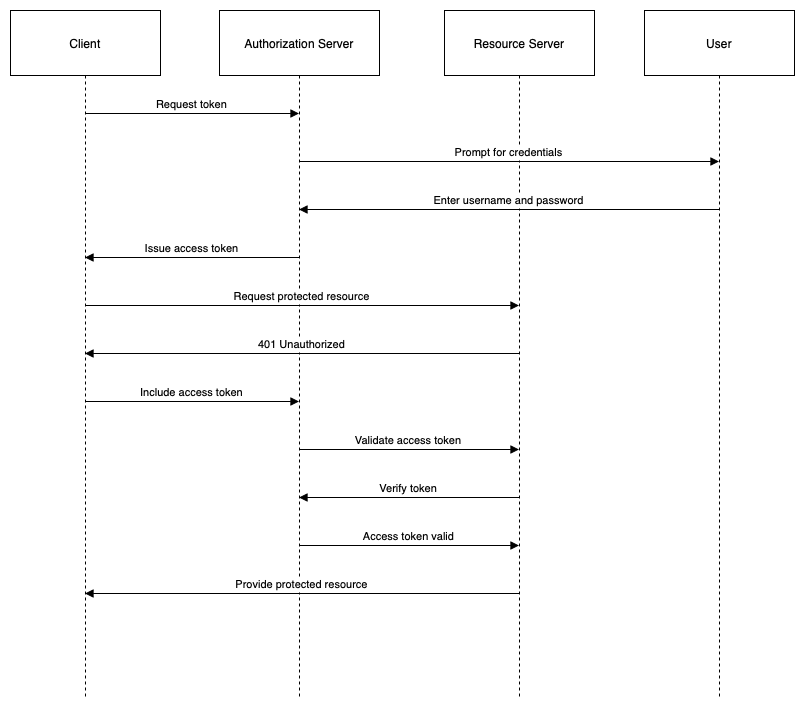

The steps of the resource owner password credentials grant are as follows:

- The client (application) requests an access token from the token endpoint (service) by presenting the resource owner’s credentials (username and password), the client identifier, and the requested scope.

- The authorization server validates the resource owner’s credentials, the client identity, and the requested scope. If successful, the authorization server issues an access token (and optionally a refresh token) to the client.

- The client requests the protected resource from the resource server (service) by presenting the access token in the HTTP Authorization header or as a query parameter.

- The resource server validates the access token and serves the requested resource to the client.

The following diagram illustrates this flow:

A typical use case for this grant type is a trusted application that has a strong relationship with the user and needs to access their data on another service, such as an email client or a banking app. For example, an email client may want to access a user’s Gmail account to send and receive emails, or a banking app may want to access a user’s bank account to perform transactions.

Some of the advantages of this grant type are:

- It is simple and straightforward, as it requires only one request to obtain an access token.

- It supports refresh tokens, which can be used to obtain new access tokens without requiring user interaction.

- It works well for applications that have a high level of trust with the user and need full access to their data.

Some of the disadvantages of this grant type are:

- It is highly insecure, as it requires the user to share their credentials with the application, which exposes them to the risk of phishing, keylogging, or credential reuse attacks.

- It violates the principle of least privilege, as it grants the application full access to the user’s account regardless of the scope of the authorization.

- It reduces the user’s control and transparency over their data and privacy, as they cannot revoke or limit the access granted to the application.

Client Credentials Grant

The client credentials grant is a grant type for applications that act on their own behalf rather than on behalf of a user. The client credentials are a pair of client identifier and client secret that are used to authenticate the client to the authorization server. The client credentials grant provides a simple and efficient way for applications to access their own resources or resources shared with them by other applications.

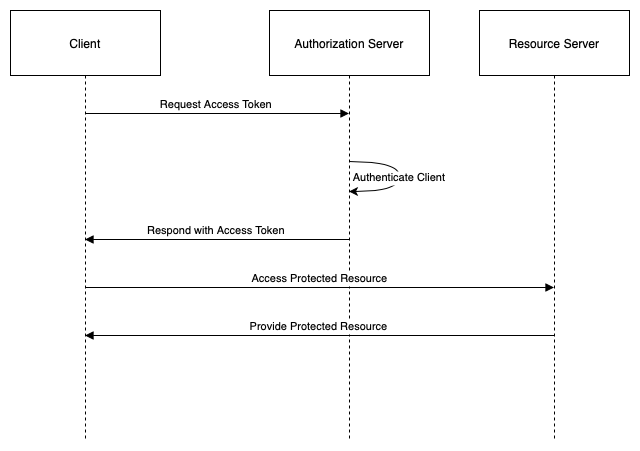

The steps of the client credentials grant are as follows:

- The client (application) requests an access token from the token endpoint (service) by presenting the client credentials (client identifier and client secret) and the requested scope.

- The authorization server validates the client credentials and the requested scope. If successful, the authorization server issues an access token to the client.

- The client requests the protected resource from the resource server (service) by presenting the access token in the HTTP Authorization header or as a query parameter.

- The resource server validates the access token and serves the requested resource to the client.

The following diagram illustrates this flow:

A typical use case for this grant type is an application that needs to access its own resources or resources shared with it by other applications. For example, a cloud service may want to access its own storage or compute resources, or a payment service may want to access a shared ledger or transaction history.

Some of the advantages of this grant type are:

- It is simple and efficient, as it requires only one request to obtain an access token.

- It does not involve user interaction, which can improve performance and user experience.

- It works well for applications that act on their own behalf or have a common trust relationship with other applications.

Some of the disadvantages of this grant type are:

- It is less secure, as it relies on the client to protect its credentials from unauthorized access or leakage.

- It does not support refresh tokens, which means the client has to request a new access token when the previous one expires.

- It does not allow for user consent or revocation, which can limit the user’s control and transparency over their data and privacy.

OAuth 2.0 Components and Terminology

In this section, I will explain some of the essential OAuth 2.0 components and terminology that are used throughout the protocol.

Access Token

An access token is a string that represents an authorization issued to the client by the authorization server. The access token is used by the client to access the protected resource from the resource server. The access token typically contains information such as the issuer, the audience, the scope, the expiration time, and other attributes.

The format and content of the access token are defined by the authorization server and are usually opaque to the client. However, some authorization servers may use a structured format such as JSON Web Token (JWT) to encode the access token. A JWT is a compact and self-contained way of securely transmitting information between parties as a JSON object. A JWT consists of three parts: a header, a payload, and a signature. The header contains metadata such as the algorithm used to sign the token. The payload contains claims such as the issuer, the audience, the scope, and other attributes. The signature is used to verify the integrity and authenticity of the token.

An example of an access token in JWT format is:

1

eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJodHRwczovL2F1dGguZXhhbXBsZS5jb20iLCJhdWQiOiJodHRwczovL2FwaS5leGFtcGxlLmNvbSIsInN1YiI6IjEyMzQ1Njc4OTAiLCJzY29wZSI6InJlYWQgd3JpdGUiLCJleHAiOjE2Mjg0MjQwMDAsImlhdCI6MTYyODQyMDQwMH0.XHxkxTq7a7fX8HkxX9a8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8

The following table shows the decoded header, payload, and signature of this token:

| Part | Value |

|---|---|

| Header | {"alg":"RS256","typ":"JWT"} |

| Payload | {"iss":"https://auth.example.com","aud":"https://api.example.com","sub":"1234567890","scope":"read write","exp":1628424000,"iat":1628420400} |

| Signature | XHxkxTq7a7fX8HkxX9a8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8 |

The access token can be presented by the client to the resource server in different ways, such as:

- In the HTTP Authorization header using the Bearer scheme:

Authorization: Bearer <token> - As a query parameter:

https://api.example.com/resource?access_token=<token> - As a form-encoded body parameter:

access_token=<token>

The resource server validates the access token by checking its signature, expiration time, audience, scope, and other attributes. If the access token is valid, the resource server serves the requested resource to the client. If the access token is invalid or expired, the resource server returns an error response with the appropriate status code and message.

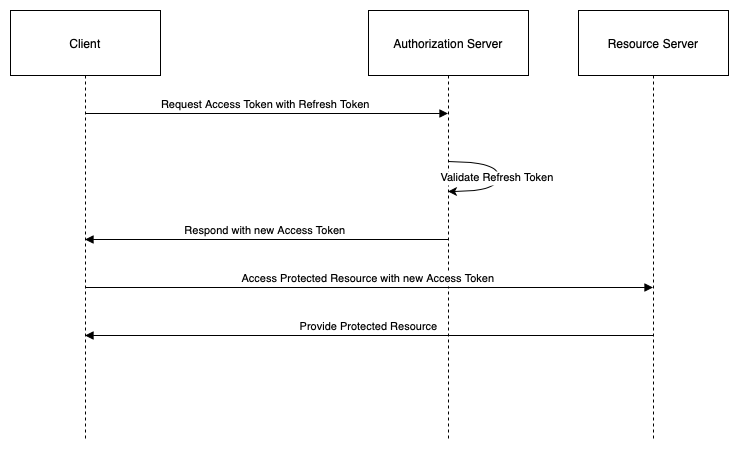

Refresh Token

A refresh token is a string that represents an authorization issued to the client by the authorization server. The refresh token is used by the client to obtain new access tokens from the authorization server without requiring user interaction. The refresh token typically has a longer lifetime than the access token and can be revoked by the authorization server or the resource owner at any time.

The format and content of the refresh token are defined by the authorization server and are usually opaque to the client. However, some authorization servers may use a structured format such as JWT to encode the refresh token.

An example of a refresh token in JWT format is:

1

eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJodHRwczovL2F1dGguZXhhbXBsZS5jb20iLCJhdWQiOiJodHRwczovL2FwaS5leGFtcGxlLmNvbSIsInN1YiI6IjEyMzQ1Njc4OTAiLCJzY29wZSI6InJlYWQgd3JpdGUiLCJleHAiOjE2Mjg0MjQwMDAsImlhdCI6MTYyODQyMDQwMH0.XHxkxTq7a7fX8HkxX9a8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8

The following table shows the decoded header, payload, and signature of this token:

| Part | Value |

|---|---|

| Header | {"alg":"RS256","typ":"JWT"} |

| Payload | {"iss":"https://auth.example.com","aud":"https://api.example.com","sub":"1234567890","scope":"read write","exp":1628424000,"iat":1628420400} |

| Signature | XHxkxTq7a7fX8HkxX9a8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8f8 |

The refresh token can be presented by the client to the authorization server in a request for a new access token. The request includes the refresh token, the client identifier, and the client secret.

The authorization server validates the refresh token, the client identity, and the requested scope. If successful, the authorization server issues a new access token (and optionally a new refresh token) to the client.

The client can use the new access token to access the protected resource from the resource server.

The following diagram illustrates this flow:

Some of the advantages of using refresh tokens are:

- They enable long-term access to user data without requiring user interaction.

- They reduce the number of times the user has to authenticate and consent to the application.

- They improve performance and user experience by avoiding unnecessary redirects and requests.

Some of the disadvantages of using refresh tokens are:

- They increase the complexity and risk of managing multiple tokens.

- They require secure storage and transmission by the client to prevent unauthorized access or leakage.

- They can be revoked by the authorization server or the resource owner at any time, which can cause unexpected errors or failures.

Scope

A scope is a string that represents a specific permission or level of access that is granted to the client by the resource owner. The scope is used by the authorization server to limit the access token’s ability to access the protected resource from the resource server. The scope typically contains information such as the type, the name, or the action of the resource.

The format and content of the scope are defined by the resource server and are usually human-readable and space-delimited. However, some resource servers may use a structured format such as URN or URI to encode the scope. A URN is a uniform resource name that identifies a resource by its name in a given namespace. A URI is a uniform resource identifier that identifies a resource by its location or representation.

An example of a scope in URN format is:

1

urn:example:api:read write delete

An example of a scope in URI format is:

1

https://api.example.com/scope/read https://api.example.com/scope/write https://api.example.com/scope/delete

The authorization server validates the scope by checking its validity, availability, and compatibility with the client and the resource owner. If the scope is valid, the authorization server obtains the resource owner’s consent for the requested scope. If successful, the authorization server issues an access token with the granted scope to the client.

The scope can be presented by the client to the resource server in the HTTP Authorization header using the Bearer scheme: Authorization: Bearer <token>

The resource server validates the scope by checking its presence and value in the access token. If the scope is valid and matches the requested resource, the resource server serves the requested resource to the client. If the scope is invalid or insufficient for the requested resource, the resource server returns an error response with the appropriate status code and message.

The following diagram illustrates this flow:

Some of the advantages of using scope are:

- They enable fine-grained control and transparency over the access granted to the client by the resource owner.

- They allow for dynamic and flexible authorization based on the type, name, or action of the resource.

- They improve security and privacy by limiting the access token’s ability to access the protected resource.

Some of the disadvantages of using scope are:

- They increase the complexity and risk of managing multiple permissions or levels of access.

- They require clear and consistent definition and documentation by the resource server to avoid confusion or ambiguity.

- They can be overridden or ignored by the authorization server or the resource server, which can cause unexpected errors or failures.

OAuth 2.0 vs. OAuth 1.0a: A Comparison

OAuth 2.0 is not a direct successor or replacement of OAuth 1.0a, but rather a new and different protocol that aims to address some of the limitations and challenges of OAuth 1.0a. OAuth 1.0a is an earlier version of OAuth that was published in 2010 and is still widely used by some services, such as Twitter and Flickr.

The main differences between OAuth 2.0 and OAuth 1.0a are:

- OAuth 2.0 supports multiple grant types for different scenarios, while OAuth 1.0a only supports one grant type, which is similar to the authorization code grant in OAuth 2.0.

- OAuth 2.0 uses access tokens and refresh tokens, while OAuth 1.0a uses access tokens and request tokens. A request token is a temporary token that is used to obtain an access token from the authorization server.

- OAuth 2.0 relies on HTTPS for security, while OAuth 1.0a uses a complex signature mechanism to sign each request with a shared secret and a nonce (a random string). A shared secret is a confidential piece of information that is known only to the client and the authorization server.

- OAuth 2.0 is more flexible and extensible, as it allows for different token formats, transport methods, and authorization flows, while OAuth 1.0a is more rigid and standardized, as it defines a specific token format, transport method, and authorization flow.

Some of the advantages of OAuth 2.0 over OAuth 1.0a are:

- It provides a better user experience, as it reduces the number of redirects and requests required for authorization.

- It simplifies the development and integration of applications, as it does not require complex signature generation and verification.

- It enables more use cases and scenarios, as it supports different grant types, token types, and device types.

Some of the disadvantages of OAuth 2.0 over OAuth 1.0a are:

- It may compromise security, as it relies on HTTPS for encryption and does not use signatures for authentication.

- It may introduce compatibility issues, as it does not have a standard specification and allows for different implementations and interpretations.

- It may require more resources and maintenance, as it involves multiple tokens, endpoints, and parameters.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we have explored the basics of OAuth 2.0, the authorization flow, the components and terminology, the common use cases and implementations, the best practices for security, and the comparison with OAuth 1.0a.

We have learned that OAuth 2.0 is a widely used protocol that enables applications to obtain limited access to user accounts on an HTTP service, such as Facebook, Google, or Twitter. It works by delegating user authentication to the service that hosts the user account, and authorizing third-party applications to access the user account.

We have also learned that understanding OAuth 2.0 is important for developers, businesses, and users alike. For developers, OAuth 2.0 simplifies the development of secure and user-friendly applications that can access various online services. For businesses, OAuth 2.0 enables them to offer their APIs to third-party developers and partners in a controlled and secure manner. For users, OAuth 2.0 gives them more control and transparency over their data and privacy.

I hope that this blog post has helped you demystify OAuth 2.0 and gain a comprehensive understanding of this protocol. I encourage you to implement OAuth 2.0 correctly to ensure both security and user convenience in your applications.

Thank you for reading!