Understanding HNSW - Hierarchical Navigable Small World

The Hierarchical Navigable Small World algorithm represents a fundamental breakthrough in approximate nearest neighbor search for high-dimensional vector spaces. Introduced by Yury Malkov and Dmitry Yashunin in 2016, HNSW addresses the critical limitation of existing similarity search methods that struggled to maintain both speed and accuracy as dataset sizes grew to millions or billions of vectors. The algorithm achieves logarithmic search complexity through a sophisticated multi-layer graph structure that separates connections by characteristic distance scales, enabling efficient navigation from coarse to fine granularity during search operations.

The significance of HNSW extends beyond its theoretical contributions to practical impact across numerous domains. Modern vector databases, recommendation systems, and large-scale machine learning applications rely heavily on HNSW’s ability to perform fast approximate nearest neighbor searches while maintaining high recall rates. The algorithm’s robustness across different data distributions, dimensionalities, and distance metrics has established it as the de facto standard for similarity search in production systems.

Historical Context and Problem Landscape

The Nearest Neighbor Search Challenge

The fundamental problem that HNSW addresses is the efficient retrieval of the K most similar items from a large collection of high-dimensional vectors. Traditional approaches to this problem fall into several categories, each with distinct limitations that become more pronounced as data scales increase. Exact search methods that guarantee finding the true nearest neighbors require examining every point in the dataset, resulting in linear time complexity that becomes computationally prohibitive for large-scale applications.

Tree-based approaches such as k-d trees and R-trees attempt to partition the search space hierarchically, enabling faster queries through efficient pruning of irrelevant regions. However, these methods suffer severely from the curse of dimensionality. As the number of dimensions increases beyond approximately 10-20, the effectiveness of spatial partitioning diminishes rapidly, and query performance degrades to nearly linear search times. This limitation makes tree-based methods unsuitable for the high-dimensional vector spaces common in modern machine learning applications.

Locality-sensitive hashing represents another approach that attempts to solve the high-dimensional search problem through probabilistic bucketing schemes. LSH methods create hash functions that map similar items to the same buckets with high probability, enabling sub-linear search times. However, achieving high recall rates typically requires maintaining multiple hash tables, leading to significant memory overhead and complex parameter tuning. The probabilistic nature of LSH also makes it difficult to provide strong accuracy guarantees.

Product quantization techniques address the memory efficiency challenge by compressing high-dimensional vectors into compact codes while preserving approximate distance relationships. While PQ methods achieve excellent memory utilization, they require substantial preprocessing time and may suffer accuracy losses due to quantization errors. The compression process also introduces computational overhead during distance calculations, limiting query throughput.

Graph-Based Proximity Search Evolution

Graph-based approaches emerged as a promising alternative that could potentially overcome the limitations of tree-based and hashing methods. The fundamental insight behind proximity graphs is that similarity relationships in high-dimensional spaces can be effectively captured through graph connectivity patterns. In a well-constructed proximity graph, each vector connects to its most similar neighbors, creating paths that enable efficient navigation toward query targets.

Early proximity graph methods achieved impressive results on certain datasets but suffered from fundamental scalability limitations. The primary challenge was that greedy routing through these graphs exhibited power-law complexity scaling, where search time increased polynomially with dataset size rather than logarithmically. This limitation arose because the graphs lacked proper hierarchical structure, forcing searches to traverse many intermediate nodes before reaching the target region.

The development of Navigable Small World graphs represented a significant advancement in addressing these scalability challenges. NSW graphs combined the local connectivity patterns of traditional proximity graphs with long-range connections that enabled rapid traversal across the entire dataset. The construction process involved inserting vectors in random order and connecting each new vector to its M closest previously inserted neighbors. This approach created hub nodes with many connections that served as bridges between different regions of the vector space.

Despite their improvements over earlier proximity graph methods, NSW graphs still exhibited polylogarithmic search complexity rather than the desired logarithmic scaling. The limitation arose from the interaction between path length and node degree along search paths. While the number of hops in a greedy search scaled logarithmically, the average degree of nodes encountered during search also increased logarithmically, resulting in an overall polylogarithmic complexity for distance computations.

Theoretical Foundations

Small World Network Theory

The theoretical foundation of HNSW draws heavily from small world network theory, which originated in sociology but found applications across diverse scientific domains. Small world networks exhibit two key properties that make them particularly suitable for efficient search operations. First, they maintain short path lengths between arbitrary node pairs, typically scaling logarithmically with network size. Second, they preserve high clustering coefficients that reflect strong local connectivity patterns.

The seminal work of Jon Kleinberg provided crucial insights into when small world networks become navigable through decentralized search algorithms. Kleinberg’s analysis demonstrated that specific probability distributions governing long-range connection formation could enable greedy routing algorithms to find logarithmically short paths using only local information. The key insight was that long-range connections must follow a power-law distribution with an exponent equal to the embedding space dimensionality to achieve optimal navigability.

Kleinberg’s model assumed vertices embedded in a low-dimensional lattice structure with both local connections to immediate neighbors and long-range connections sampled according to distance-dependent probabilities. When the probability of connecting to a vertex at distance d follows d^(-α), the model exhibits navigable properties only when α equals the lattice dimensionality. For other values of α, greedy routing either fails to utilize long-range connections effectively or becomes trapped in local minima.

The significance of Kleinberg’s result extends beyond its immediate mathematical implications to provide design principles for constructing navigable graph structures. The work established that achieving logarithmic search complexity requires careful balance between local and long-range connectivity patterns. Too many short connections limit the ability to make long-distance progress, while too many long connections make it difficult to converge accurately to target locations.

Skip List Algorithmic Principles

Skip lists provide the second major theoretical foundation for HNSW through their hierarchical probabilistic structure. Introduced by William Pugh in 1990, skip lists achieve logarithmic search, insertion, and deletion operations through a multi-level linked list architecture. The fundamental innovation of skip lists lies in their probabilistic level assignment scheme, where each element appears in progressively fewer levels as height increases.

The construction of skip lists follows a simple probabilistic rule where each element appears in level i+1 with probability p given its presence in level i. This scheme creates an exponential decay in level populations, ensuring that higher levels contain progressively fewer elements while maintaining connectivity across the entire structure. The parameter p typically takes values between 0.25 and 0.5, with p=0.5 providing optimal theoretical properties for most applications.

Search operations in skip lists begin at the highest level and proceed horizontally until encountering an element greater than or equal to the target value. At that point, the search descends to the next lower level and continues the horizontal traversal. This process repeats until reaching the bottom level, where the exact target location can be determined. The multi-level structure enables the algorithm to make large jumps at higher levels while maintaining precision at lower levels.

The expected search path length in a skip list scales as O(log n) due to the exponential level structure. At each level, the expected horizontal distance traveled before descending is bounded by 1/p, which is constant. Since the expected maximum level scales logarithmically with the number of elements, the total expected search time achieves logarithmic complexity. This analysis assumes ideal probabilistic conditions, but practical implementations typically achieve performance close to theoretical expectations.

Navigable Small World Graph Properties

Navigable Small World graphs extend the small world concept specifically for similarity search applications in metric spaces. Unlike Kleinberg’s lattice-based model, NSW graphs operate in arbitrary metric spaces without requiring knowledge of the underlying data distribution. The construction process involves incremental insertion of elements with connection establishment based purely on distance relationships in the original metric space.

The navigability properties of NSW graphs arise from their specific construction methodology rather than predetermined connection probability distributions. When inserting a new element, the algorithm searches for its closest neighbors among previously inserted elements using the existing graph structure. This bootstrapping approach creates long-range connections naturally as early-inserted elements tend to have high degrees and serve as hubs for later insertions.

The resulting graph structure exhibits small world properties with average path lengths scaling logarithmically and high clustering coefficients due to the proximity-based connection criteria. However, the degree distribution tends to be highly skewed, with early-inserted elements accumulating many more connections than later additions. This heterogeneity actually contributes to navigability by creating hub nodes that serve as efficient routing points for long-distance traversals.

The routing process in NSW graphs follows a greedy strategy where each step moves to the neighbor closest to the query target. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the graph’s ability to provide good local routing choices at each step. The proximity-based construction ensures that local neighborhoods contain progressively closer neighbors as the search approaches the target region, enabling effective convergence in most cases.

Core Algorithm Architecture

Hierarchical Layer Structure Design

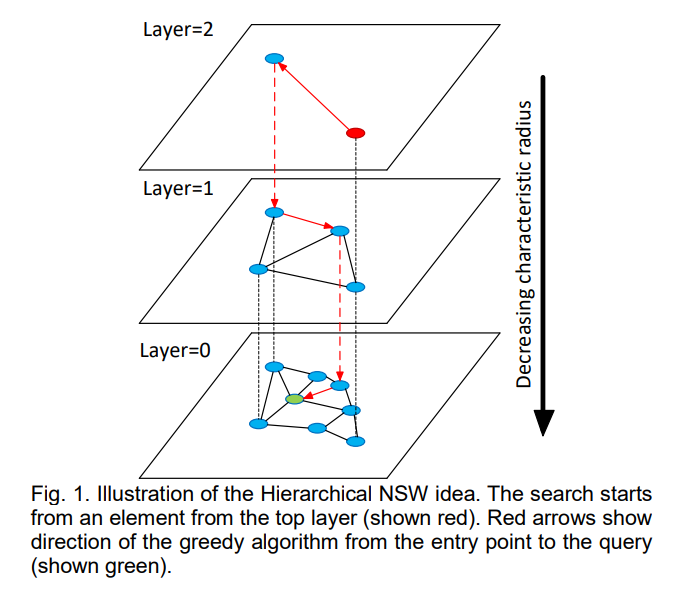

The central innovation of HNSW lies in its hierarchical decomposition of the proximity graph into multiple layers with distinct connectivity patterns. This architectural choice addresses the fundamental limitation of NSW graphs by separating connections based on their characteristic distance scales. The layer structure enables searches to begin with long-range navigation at higher levels before transitioning to precise local search at the bottom level.

The layer assignment for each element follows an exponential probability distribution that mirrors the skip list construction principle. When inserting a new element, the algorithm first determines its maximum layer level using the formula l = floor(-ln(uniform(0,1)) * mL), where mL is a normalization parameter that controls the expected number of layers. This probabilistic assignment ensures that higher layers contain exponentially fewer elements while maintaining proper connectivity.

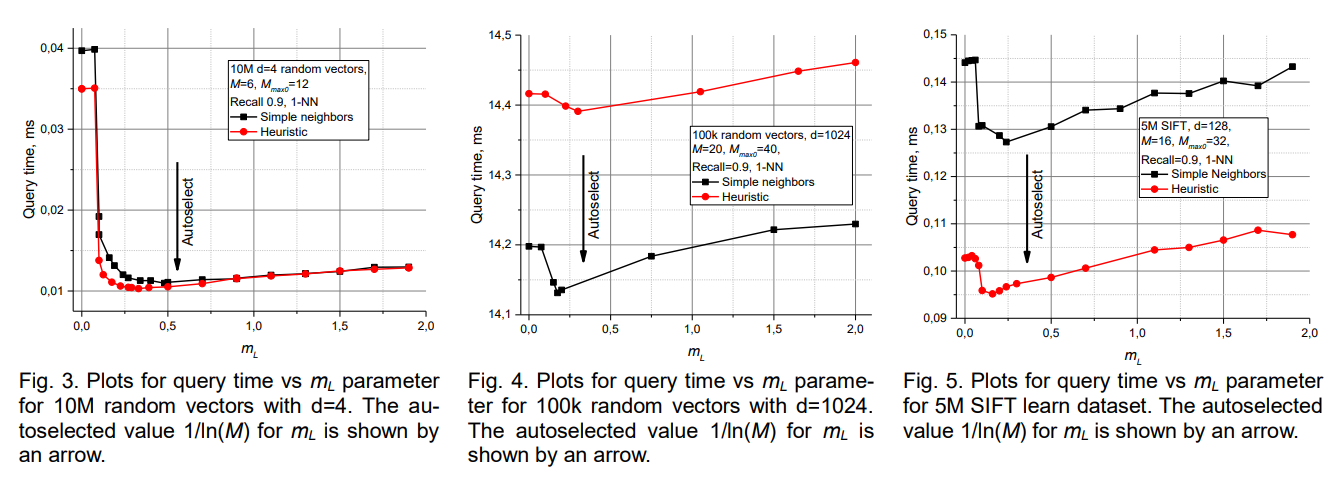

The parameter mL plays a crucial role in balancing the tradeoff between search efficiency and construction complexity. Smaller values of mL create more layers with greater separation between levels, potentially improving search performance but increasing construction time and memory usage. Larger values reduce the number of layers but may limit the benefits of hierarchical navigation. Empirical analysis suggests that mL = 1/ln(M) provides optimal performance, where M is the maximum number of connections per element.

Each layer maintains its own proximity graph with connections established independently based on the element subset present at that level. The connectivity patterns vary significantly between layers, with higher layers exhibiting longer average connection distances due to the reduced element density. This natural separation of distance scales occurs automatically through the probabilistic layer assignment without requiring explicit distance thresholding.

The layer structure creates a natural hierarchy where searches can quickly traverse large portions of the vector space at higher levels before descending to more populated lower levels for precise navigation. This design enables logarithmic search complexity by ensuring that the total work performed across all layers remains bounded as the dataset size increases.

Construction Algorithm Mechanics

The construction process for HNSW follows an incremental insertion strategy where each new element is added to the existing multi-layer structure through a carefully orchestrated sequence of operations. The algorithm maintains the global entry point, which serves as the starting location for all search operations and typically corresponds to one of the first inserted elements or an element reaching a high layer level.

The insertion process begins by determining the new element’s maximum layer level through the probabilistic assignment scheme. The algorithm then performs a multi-phase search starting from the global entry point at the highest existing layer. During the first phase, the search proceeds through layers above the new element’s maximum level using a simple greedy strategy with ef=1, meaning only the single closest neighbor is tracked at each step.

This initial search phase serves to identify good entry points for the layers where the new element will actually be inserted. The greedy navigation with minimal beam width is sufficient for this coarse positioning because the primary goal is reaching the appropriate region of the vector space rather than finding the exact optimal neighbors. The reduced computational overhead of single-candidate search makes this phase very efficient.

When the search reaches a layer at or below the new element’s maximum level, the algorithm transitions to the second phase with enhanced search capabilities. The search beam width increases to efConstruction, allowing the algorithm to maintain multiple candidate neighbors simultaneously. This expansion provides greater robustness against local minima and improves the quality of neighbor selection for connection establishment.

The neighbor selection process employs sophisticated heuristics that go beyond simple distance-based ranking. Algorithm 4 in the original paper presents a diversity-aware selection method that considers not only the distance between candidates and the query element but also the distances between candidate elements themselves. This approach helps maintain global connectivity by avoiding purely local clustering that could fragment the graph structure.

Search Algorithm Implementation

The search algorithm in HNSW implements a multi-layer greedy traversal strategy that efficiently navigates from coarse to fine granularity while maintaining bounded computational complexity. The process begins at the global entry point in the highest layer and follows a structured descent through progressively more detailed layers until reaching the bottom level where all elements reside.

The initial search phase operates at layers above the target level (typically layer 0 for query operations) using a streamlined greedy approach with ef=1. This configuration prioritizes speed over thoroughness since the goal is rapid positioning rather than exhaustive local search. The algorithm maintains a single best candidate at each step and moves greedily toward the query target by examining the neighborhood of the current best element.

The greedy movement strategy evaluates all neighbors of the current position and selects the one closest to the query target as the next position. This process continues until reaching a local minimum where no neighbor is closer to the query than the current position. The local minimum condition indicates that further improvement requires transitioning to a more detailed layer with additional connectivity options.

Upon reaching layer 0, the algorithm switches to an enhanced search mode with ef > 1 to identify the final answer candidates. The expanded beam width enables exploration of multiple promising paths simultaneously, reducing the risk of premature convergence to suboptimal solutions. The algorithm maintains a dynamic priority queue of candidates and systematically expands the search frontier until identifying the K closest neighbors.

The search termination criteria ensure both efficiency and accuracy by balancing exploration thoroughness with computational cost. The algorithm continues expanding the search frontier until either finding the desired number of neighbors or exhausting all promising candidates within the specified search radius. This adaptive termination strategy provides strong performance guarantees while avoiding unnecessary computation.

Neighbor Selection Heuristics

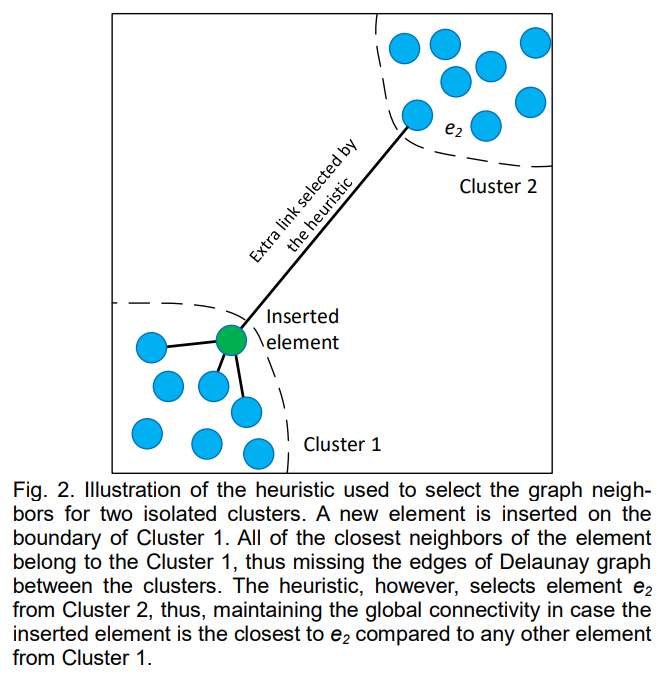

The neighbor selection component of HNSW represents one of its most sophisticated algorithmic innovations, addressing the critical challenge of maintaining graph connectivity while limiting the number of connections per element. The heuristic approach goes beyond naive distance-based selection to consider the global graph structure and connectivity patterns.

Algorithm 4 presents the advanced neighbor selection heuristic that prioritizes diversity among selected neighbors while maintaining proximity requirements. The algorithm operates by iteratively examining candidate neighbors in order of increasing distance from the target element. For each candidate, it evaluates whether the candidate provides a valuable addition to the current neighbor set based on its relationship to already selected neighbors.

The key insight behind the heuristic is that effective neighbor selection should create connections that serve the dual purposes of local accuracy and global connectivity. Purely distance-based selection can create highly clustered local neighborhoods that fail to provide adequate routing options for searches originating from distant regions. The heuristic addresses this limitation by favoring candidates that are closer to the target element than to any previously selected neighbor.

This relative proximity criterion helps maintain the relative neighborhood graph property, which ensures that the resulting graph structure supports efficient greedy routing. The relative neighborhood graph represents a well-studied concept in computational geometry that captures essential connectivity patterns for decentralized search while avoiding redundant connections that would increase memory usage without improving search performance.

The heuristic includes additional parameters that control its behavior in specific scenarios. The extendCandidates parameter enables expansion of the candidate set to include neighbors of the initial candidates, which can be beneficial for highly clustered data where the immediate neighborhood may not provide sufficient diversity. The keepPrunedConnections parameter allows retention of some distance-based selections even after applying the diversity criteria.

Parameter Analysis and Optimization

Critical Parameter Relationships

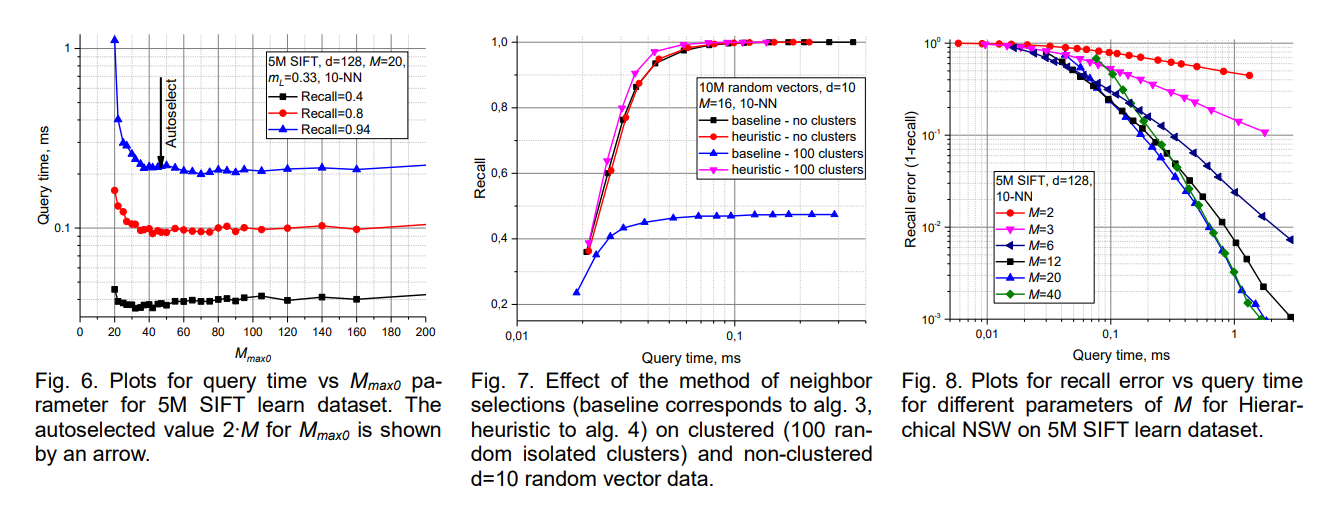

The performance characteristics of HNSW depend critically on several key parameters that control different aspects of the algorithm’s behavior. Understanding the interactions between these parameters is essential for achieving optimal performance across different types of datasets and query requirements. The primary parameters include M (maximum connections per element), mL (layer generation factor), Mmax0 (maximum connections at layer 0), and efConstruction (search beam width during construction).

The parameter M controls the fundamental tradeoff between memory usage and search quality by determining how many neighbors each element can maintain in layers above level 0. Larger values of M provide more routing options during search operations, potentially improving recall and reducing the risk of getting trapped in local minima. However, increased connectivity also leads to higher memory consumption and longer construction times due to the need to evaluate more neighbors during each search step.

Empirical analysis reveals that optimal M values typically range between 5 and 48, with the ideal choice depending on the dimensionality and clustering characteristics of the data. Lower-dimensional datasets often perform well with smaller M values around 5-12, while high-dimensional data may benefit from larger values in the range of 16-48. The relationship between M and data characteristics reflects the fundamental tradeoff between local search precision and global connectivity maintenance.

The layer generation parameter mL governs the expected number of layers in the hierarchical structure through its control over the exponential probability distribution used for level assignment. The recommended value mL = 1/ln(M) provides a balance between layer separation and construction efficiency. This choice ensures that adjacent layers have approximately 1/M overlap in their element populations, creating sufficient differentiation between levels while maintaining connectivity.

Smaller values of mL create more aggressive layer separation with fewer elements promoted to higher levels. This configuration can improve search performance by enabling larger jumps at higher levels but may increase construction complexity and reduce robustness to variations in data distribution. Larger mL values create more conservative layering with greater overlap between adjacent levels, potentially sacrificing some search efficiency for improved stability.

Memory and Construction Complexity Analysis

The memory consumption of HNSW scales linearly with the dataset size, making it suitable for large-scale applications where memory efficiency is important. The total memory requirement can be expressed as approximately (Mmax0 + mL * Mmax) * bytes_per_link per element, where Mmax represents the maximum connections allowed at layers above level 0. For typical parameter settings, this translates to roughly 60-450 bytes per element for the graph structure alone, excluding the storage required for the original vector data.

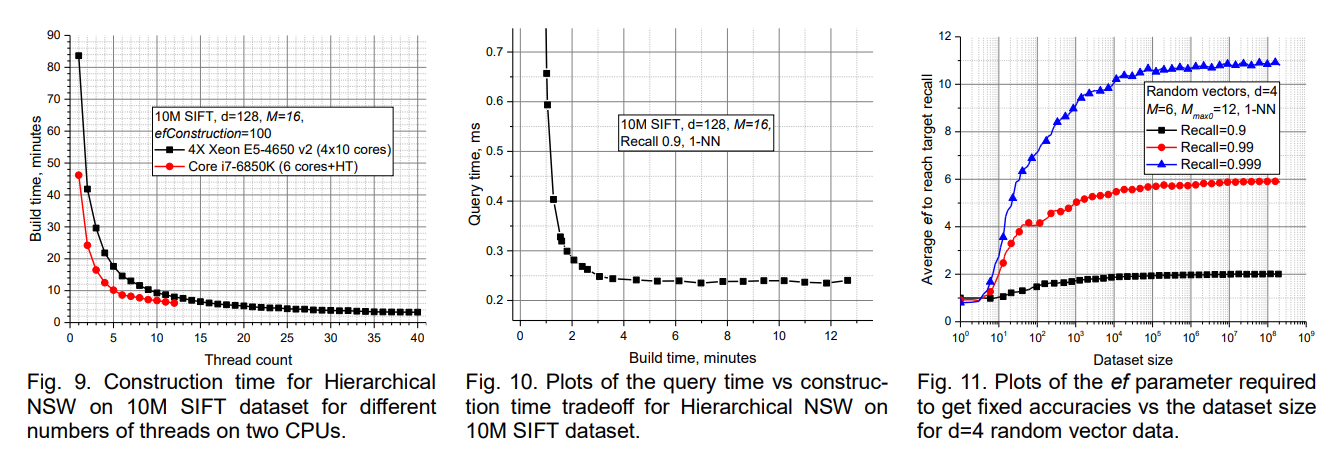

The construction time complexity of HNSW exhibits favorable scaling properties that make it practical for building indexes on large datasets. Theoretical analysis suggests O(N log N) complexity for construction on relatively low-dimensional data, where N represents the number of elements. This scaling behavior arises because each element insertion requires searching through the existing structure, which takes logarithmic time on average, and this process must be repeated for all N elements.

The construction process can be efficiently parallelized across multiple threads with minimal synchronization overhead. The key insight enabling effective parallelization is that element insertions can proceed concurrently as long as they operate on different regions of the graph structure. The probabilistic nature of the construction process helps distribute the computational load evenly across threads while avoiding excessive contention for shared data structures.

Practical construction times depend heavily on the implementation details and hardware characteristics, but the original authors report building a 10-million element SIFT dataset in approximately 3 minutes using a 4X 2.4 GHz 10-core Xeon processor with efConstruction=100. The construction time exhibits a reasonable tradeoff relationship with final index quality, where higher efConstruction values produce better graphs at the cost of longer build times.

The incremental nature of HNSW construction provides significant advantages for dynamic applications where new elements must be added to existing indexes without rebuilding the entire structure. The insertion process for new elements follows the same algorithmic steps as initial construction, enabling seamless index updates as data collections evolve over time.

Search Quality and Performance Tradeoffs

The search performance of HNSW can be finely tuned through the ef parameter, which controls the beam width during query operations. This parameter enables users to balance between search speed and recall quality according to their specific application requirements. Smaller ef values prioritize speed by maintaining narrower search beams, while larger values improve recall by exploring more thoroughly around the query target.

The relationship between ef and search quality follows a predictable pattern where recall increases monotonically with ef until reaching a saturation point beyond which additional beam width provides diminishing returns. The saturation point typically occurs when ef becomes large enough to overcome the local minima that represent the primary source of recall errors in greedy graph search algorithms.

Optimal ef values vary significantly across different datasets and query types, making adaptive parameter selection an important consideration for practical applications. High-dimensional datasets with complex clustering patterns may require larger ef values to achieve acceptable recall rates, while simpler data distributions can often achieve excellent results with smaller beam widths.

The computational cost of search operations scales approximately linearly with the ef parameter, making the speed-quality tradeoff highly controllable. This scalability property enables applications to implement adaptive search strategies that adjust ef based on query urgency, system load, or user quality requirements. Real-time applications might use smaller ef values during peak traffic periods while batch processing jobs could employ larger values for maximum accuracy.

The recall characteristics of HNSW searches depend not only on the ef parameter but also on the quality of the underlying graph structure, which is determined by the construction parameters. Well-constructed graphs with appropriate M and efConstruction values typically achieve recall rates above 95% even with moderate ef settings, while poorly constructed graphs may struggle to achieve acceptable recall regardless of search effort.

Implementation Considerations

Memory Layout and Cache Efficiency

Efficient HNSW implementations require careful attention to memory layout patterns that minimize cache misses during graph traversal operations. The graph structure consists of nodes with variable numbers of outgoing connections, creating irregular memory access patterns that can significantly impact performance if not properly managed. Modern implementations employ several strategies to improve cache locality and reduce memory bandwidth requirements.

One effective approach involves storing connection lists in contiguous memory blocks with predictable access patterns. Rather than using pointer-based representations that scatter connections throughout memory, optimized implementations pack neighbor lists into dense arrays that can be traversed efficiently during search operations. This organization reduces the number of cache lines accessed per search step and improves prefetching effectiveness.

The multi-layer structure of HNSW provides opportunities for additional memory optimizations through careful data placement strategies. Elements that appear in higher layers are accessed more frequently during search operations, making them good candidates for placement in faster memory tiers or cache-friendly locations. Some implementations maintain separate storage pools for different layer levels to optimize access patterns.

Distance computation represents another critical performance bottleneck that benefits from memory layout optimization. Storing vectors in formats that enable efficient SIMD operations can provide substantial speedups, particularly for common distance metrics like Euclidean distance or cosine similarity. Aligned memory layouts that match SIMD register sizes enable vectorized distance calculations that process multiple dimensions simultaneously.

Thread-local caching strategies can further improve performance in multi-threaded environments by reducing contention for shared data structures. Search operations maintain temporary data structures like priority queues and visited node sets that can be allocated from thread-local pools to avoid synchronization overhead. This approach enables near-linear scaling with the number of threads for concurrent query processing.

Distance Computation Optimization

The efficiency of distance calculations has a direct impact on overall HNSW performance since search operations may evaluate hundreds or thousands of distances per query. Optimizing these computations requires considering both algorithmic approaches and low-level implementation details that can significantly affect throughput and latency characteristics.

For high-dimensional vectors, SIMD instructions provide substantial performance improvements by enabling parallel computation across multiple vector dimensions. Modern processors support 256-bit or 512-bit SIMD registers that can process 8-16 floating-point values simultaneously, depending on precision requirements. Effective use of SIMD requires careful attention to memory alignment and data layout to ensure efficient loading of vector components.

Distance metric selection influences both accuracy and computational efficiency, with some metrics offering better optimization opportunities than others. Euclidean distance benefits from SIMD vectorization and can avoid expensive square root operations when only relative rankings matter. Cosine similarity requires additional normalization steps but can be optimized through precomputed vector norms and efficient dot product implementations.

Approximate distance computation techniques provide another way for performance improvement in scenarios where exact distances are unnecessary for routing decisions. Early termination strategies can abort distance calculations once they exceed certain thresholds, reducing computation for obviously inferior candidates. Quantized distance approximations using lower-precision arithmetic can provide significant speedups with minimal impact on search quality.

The interaction between distance computation and memory access patterns creates additional optimization opportunities. Blocked distance calculation approaches that compute multiple distances simultaneously can improve cache utilization by amortizing vector loading costs across multiple comparisons. This technique is particularly effective when evaluating distances to multiple neighbors of the same graph node.

Concurrent Access and Thread Safety

HNSW implementations must address several concurrency challenges to enable efficient multi-threaded query processing and dynamic index updates. The graph structure involves complex pointer relationships and mutable connection lists that require careful synchronization to maintain correctness under concurrent access. Different implementation strategies offer varying tradeoffs between performance and complexity.

Read-heavy workloads, which are common in production similarity search applications, can achieve excellent parallel scalability through lock-free reading techniques. Since graph traversal operations only require reading connection information without modifying the underlying structure, multiple search threads can operate simultaneously without interference. This approach requires careful attention to memory ordering and atomic operations to ensure consistency.

Dynamic updates present greater synchronization challenges since insertion operations must modify both local connection lists and the global graph structure. Fine-grained locking strategies that protect individual nodes or regions of the graph can provide better concurrency than coarse-grained approaches but require careful deadlock avoidance and lock ordering protocols. Reader-writer locks may be appropriate for workloads with mixed read and update operations.

Lock-free and wait-free algorithms represent advanced approaches that eliminate blocking entirely through sophisticated atomic operations and memory management techniques. These implementations can achieve superior scalability but require significant complexity to handle issues like memory reclamation and ABA problems. The performance benefits may justify the implementation complexity for high-throughput applications.

Copy-on-write strategies provide an alternative approach that maintains multiple versions of the graph structure to support concurrent readers and writers. Updates create new versions of modified portions while leaving existing versions intact for ongoing readers. This approach trades memory overhead for simplified synchronization but can be effective for applications with predictable update patterns.

Experimental Validation and Performance Analysis

Benchmark Methodology and Dataset Characteristics

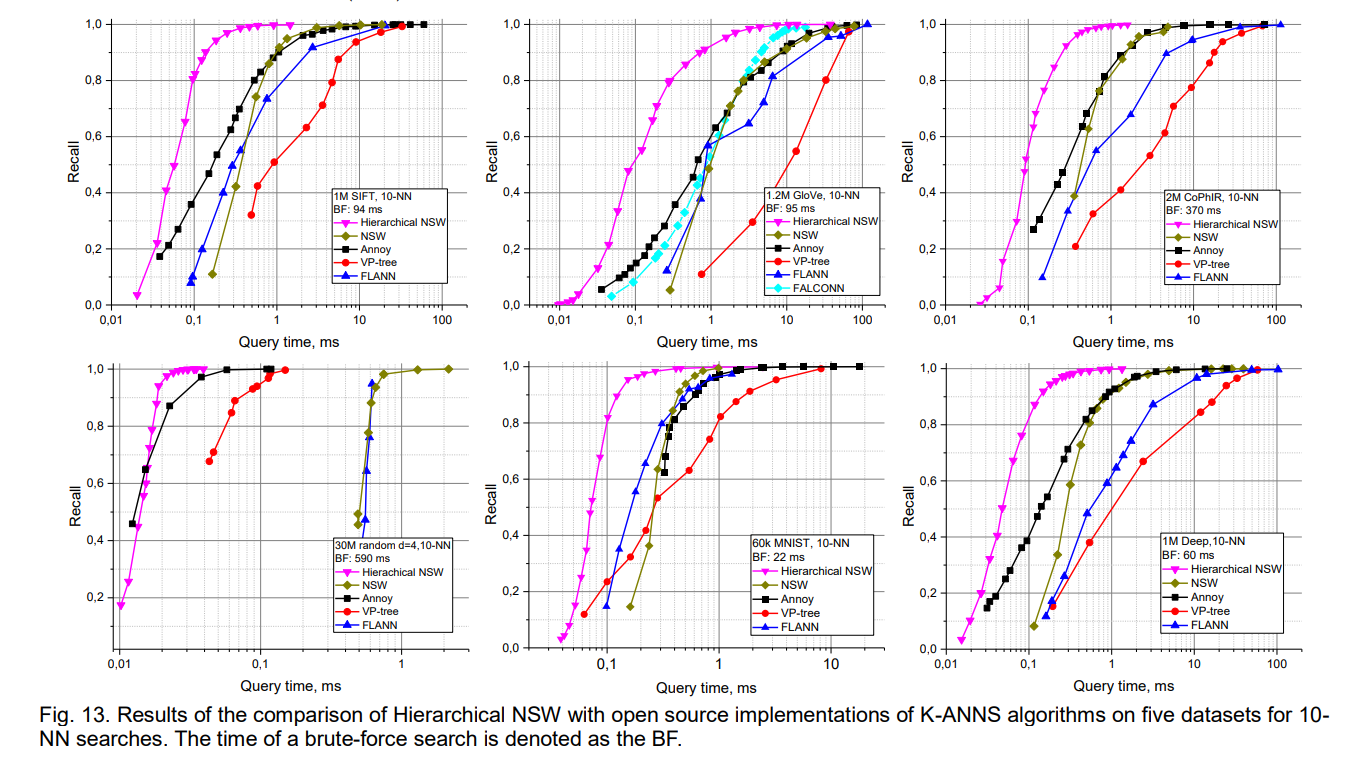

The experimental evaluation of HNSW requires carefully designed benchmarks that assess performance across diverse data types, dimensionalities, and query patterns. The original paper demonstrates a comprehensive evaluation methodology that compares HNSW against state-of-the-art alternatives using standardized datasets and metrics. This approach enables objective assessment of the algorithm’s strengths and limitations across different application domains.

The benchmark datasets span a range of characteristics that reflect real-world similarity search scenarios. The SIFT dataset consists of 128-dimensional image feature vectors extracted from natural images, representing a common computer vision application. GloVe embeddings provide 100-dimensional word vectors trained on Twitter data, reflecting natural language processing use cases. The CoPhIR dataset contains 272-dimensional MPEG-7 features from image collections, demonstrating performance on multimedia retrieval tasks.

Synthetic datasets complement the real-world data by enabling controlled evaluation of specific algorithmic properties. Random hypercube vectors with varying dimensionalities test performance scaling with dimension count, while clustered datasets evaluate robustness to non-uniform data distributions. These controlled experiments help isolate the impact of different data characteristics on algorithm performance.

The evaluation metrics focus on the fundamental tradeoffs between search speed, accuracy, and memory consumption that characterize approximate nearest neighbor algorithms. Recall measures the fraction of true nearest neighbors successfully identified by the algorithm, while query time captures the computational cost of search operations. Memory usage quantifies the storage overhead required for the index structure beyond the original vector data.

The experimental methodology employs standardized query sets extracted randomly from each dataset to ensure representative performance measurement. Multiple runs with different random seeds help quantify performance variability and establish confidence intervals for reported results. The comparison includes both algorithmic complexity analysis and absolute performance measurements on specific hardware configurations.

Scalability Analysis and Complexity Validation

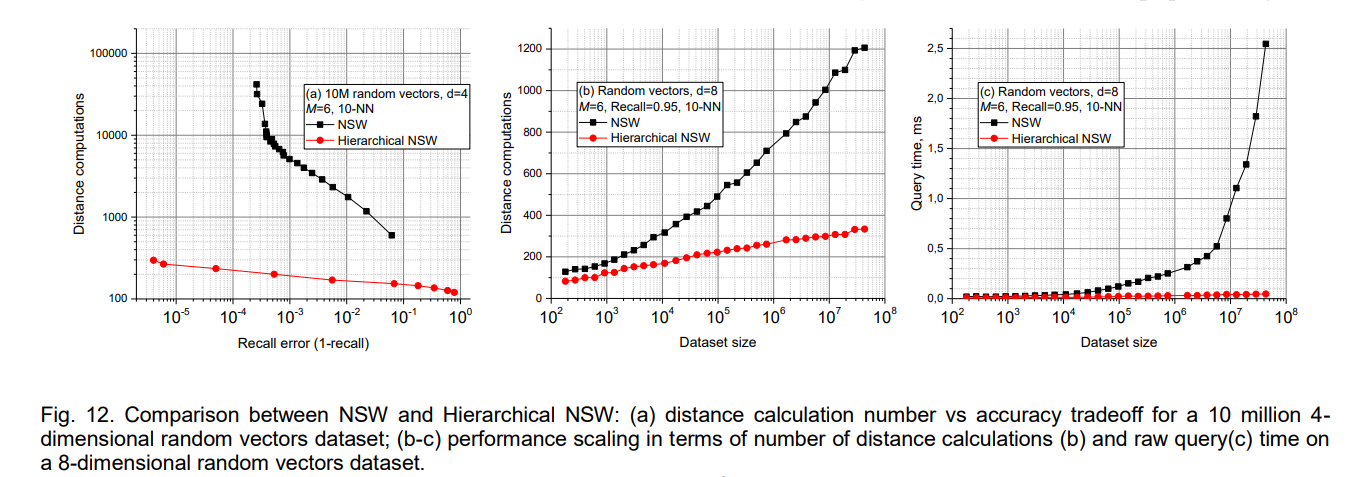

The scalability analysis demonstrates HNSW’s logarithmic search complexity through systematic evaluation across datasets of varying sizes. The experiments measure both the number of distance computations and actual query times as functions of dataset size, revealing the algorithmic efficiency gains relative to linear search and competing methods. These results validate the theoretical complexity analysis while highlighting practical performance characteristics.

For low-dimensional data, the experimental results clearly demonstrate logarithmic scaling behavior that matches theoretical predictions. The number of distance computations per query grows slowly with dataset size, confirming that the hierarchical structure effectively reduces the search space at each layer. The actual query times exhibit similar scaling patterns, though with additional factors related to memory access patterns and cache effects.

High-dimensional datasets present more complex scaling behavior due to the intrinsic properties of high-dimensional spaces and the limitations of proximity-based routing. While HNSW maintains significant advantages over competing methods, the logarithmic scaling may become less pronounced in very high dimensions where the concept of nearest neighbors becomes less meaningful due to concentration of measure phenomena.

The construction time analysis reveals favorable O(N log N) scaling for index building operations, making HNSW practical for large-scale applications where index construction time is a critical consideration. The parallel construction capabilities further improve the practical scalability by enabling effective utilization of multi-core processors and distributed computing resources.

Memory usage scaling exhibits the expected linear relationship with dataset size, confirming that HNSW’s storage requirements remain practical even for very large collections. The memory efficiency compares favorably to tree-based methods while providing superior search performance, making HNSW an attractive choice for memory-constrained environments.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The comparative analysis positions HNSW’s performance relative to other state-of-the-art approximate nearest neighbor algorithms across multiple dimensions of evaluation. The results demonstrate consistent superiority across diverse datasets and query patterns while highlighting specific scenarios where alternative approaches might be preferable.

Against tree-based methods like FLANN, HNSW shows dramatic performance advantages on high-dimensional datasets where tree methods suffer from the curse of dimensionality. The performance gap becomes increasingly pronounced as dimensionality increases, with HNSW maintaining fast search times while tree methods degrade toward linear search behavior. However, FLANN may still provide competitive performance on very low-dimensional data where tree partitioning remains effective.

Locality-sensitive hashing methods present a different performance profile characterized by fast query times but lower recall rates and significant memory overhead for achieving high accuracy. HNSW typically achieves better recall-speed tradeoffs than LSH while requiring less memory for equivalent performance levels. The deterministic nature of HNSW’s construction also provides more predictable performance characteristics compared to the probabilistic behavior of LSH schemes.

Product quantization algorithms offer superior memory efficiency through vector compression but often sacrifice query speed and accuracy. HNSW’s higher memory consumption is offset by significantly faster search times and better recall characteristics. The combination of HNSW with product quantization represents an interesting hybrid approach that can achieve both memory efficiency and search performance.

The comparison with the baseline NSW algorithm clearly demonstrates the benefits of the hierarchical structure. HNSW consistently outperforms NSW across all evaluated scenarios, with particularly dramatic improvements on low-dimensional data where NSW suffers from inefficient routing patterns. The logarithmic versus polylogarithmic complexity difference becomes increasingly important as dataset sizes grow.

Limitations and Future Directions

Algorithmic Limitations and Assumptions

Despite its impressive performance characteristics, HNSW operates under several assumptions and limitations that affect its applicability to certain problem domains. Understanding these constraints is crucial for making informed decisions about when HNSW represents the optimal choice versus alternative approaches. The algorithm’s effectiveness depends fundamentally on the existence of meaningful proximity relationships in the underlying vector space.

The greedy routing strategy that underlies HNSW’s search algorithm can become trapped in local minima when the graph structure fails to provide adequate routing options toward the global optimum. While the multi-layer hierarchy and beam search with ef > 1 mitigate this issue significantly, pathological cases can still occur, particularly in highly clustered or discontinuous data distributions. These limitations manifest as reduced recall rates that cannot be overcome simply by increasing search effort.

The distance metric assumptions embedded in HNSW’s design may limit its effectiveness for certain similarity measures or specialized distance functions. The algorithm assumes metric properties like triangle inequality and symmetric distances, which enable effective greedy routing decisions. Non-metric similarity measures or asymmetric distance functions may violate these assumptions and lead to degraded performance or convergence issues.

High-dimensional data presents fundamental challenges that affect all proximity-based search methods, including HNSW. As dimensionality increases, the relative differences between distances to different points become smaller due to concentration of measure effects. This phenomenon can make it difficult to distinguish between truly similar and dissimilar items, reducing the effectiveness of any distance-based search strategy.

The probabilistic construction process, while generally robust, can occasionally produce suboptimal graph structures that negatively impact search performance. The layer assignment scheme may create insufficient separation between levels or result in disconnected components that prevent effective routing. While these occurrences are rare, they highlight the inherent variability in performance that characterizes probabilistic data structures.

Distributed Systems and Scalability Challenges

The hierarchical structure of HNSW creates specific challenges for distributed implementations that require careful consideration of system architecture and communication patterns. Unlike the flat NSW structure that supports natural partitioning schemes, HNSW’s layered organization concentrates critical routing information in higher layers that must be accessible to all search operations.

The global entry point represents a particular bottleneck for distributed systems since all searches must begin from this single location. Replicating the entry point across multiple nodes helps with availability and load distribution but creates consistency challenges when the index structure evolves through dynamic updates. Alternative entry point selection strategies could potentially alleviate this limitation while maintaining search effectiveness.

Load balancing becomes more complex in hierarchical structures where different layers have different access patterns and computational requirements. Higher layers receive more traffic since they serve as entry points for all searches, while lower layers experience more localized access patterns. Effective load balancing must account for these non-uniform access patterns while maintaining reasonable communication overhead.

Data partitioning strategies for distributed HNSW must balance between maintaining local connectivity within partitions and providing sufficient inter-partition connections for global reachability. Simple hash-based partitioning may create isolated clusters that prevent effective routing, while more sophisticated partitioning schemes require additional computational overhead and complexity.

The communication overhead associated with distributed search operations can become significant, particularly for high-recall queries that require extensive graph traversal. Minimizing inter-node communication while maintaining search quality represents a fundamental tradeoff that affects the scalability of distributed implementations.

Research Directions and Algorithmic Improvements

Several promising research directions could address current limitations and extend HNSW’s applicability to new problem domains. Dynamic optimization techniques could adapt the graph structure continuously based on query patterns and data distribution changes, potentially improving performance for evolving datasets and workloads.

Learned index approaches represent an emerging area where machine learning techniques could enhance traditional index structures. Neural networks could potentially learn better layer assignment strategies, connection selection heuristics, or routing decisions that outperform the current probabilistic and greedy approaches. However, such approaches would need to maintain the simplicity and efficiency that make HNSW attractive for production use.

Hardware-specific optimizations could leverage emerging processor architectures and memory hierarchies to achieve better performance. GPU implementations could potentially accelerate distance computations and parallel search operations, while specialized vector processing units might enable more efficient similarity calculations. These optimizations require careful consideration of memory access patterns and computational characteristics.

Approximate distance computation techniques could reduce the computational overhead of search operations without significantly impacting accuracy. Learning-based distance approximations or quantization schemes specifically designed for HNSW could provide substantial speedups for high-dimensional or computationally expensive distance metrics.

Multi-modal and heterogeneous data support represents another important research direction as applications increasingly require similarity search across different data types and modalities. Extending HNSW to handle mixed data types or multiple distance metrics simultaneously could broaden its applicability to complex real-world scenarios.

Conclusion

The Hierarchical Navigable Small World algorithm represents a fundamental advancement in approximate nearest neighbor search that has transformed the landscape of similarity search applications. By combining insights from small world network theory with the hierarchical structure of skip lists, HNSW achieves logarithmic search complexity while maintaining practical efficiency and implementation simplicity. The algorithm’s robust performance across diverse datasets, dimensionalities, and distance metrics has established it as the foundation for modern vector databases and large-scale similarity search systems.

The theoretical contributions of HNSW extend beyond its immediate practical applications to provide deeper insights into the principles of navigable graph construction and probabilistic data structures. The careful balance between local connectivity and global reachability achieved through the layer hierarchy demonstrates how sophisticated algorithmic design can overcome fundamental scalability limitations that plagued earlier approaches.

The experimental validation presented in the original paper and subsequent research confirms HNSW’s superior performance characteristics while highlighting areas for continued improvement. The algorithm’s consistent advantages over alternative methods across multiple evaluation criteria support its adoption as the de facto standard for approximate nearest neighbor search in production systems.

Looking forward, HNSW provides a solid foundation for addressing emerging challenges in similarity search, including dynamic datasets, specialized hardware architectures, and multi-modal applications. The algorithmic principles underlying HNSW’s success will likely continue to influence the development of future similarity search methods and graph-based data structures.

The impact of HNSW extends beyond its immediate technical contributions to enable new applications and capabilities in machine learning, information retrieval, and data management. As the volume and complexity of high-dimensional data continue to grow, efficient similarity search algorithms like HNSW become increasingly critical for extracting meaningful insights and enabling intelligent applications.

References

Research Papers

- Malkov, Y. A., & Yashunin, D. A. (2018). Efficient and robust approximate nearest neighbor search using Hierarchical Navigable Small World graphs. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 42(4), 824-836.

- Pugh, W. (1990). Skip lists: a probabilistic alternative to balanced trees. Communications of the ACM, 33(6), 668-676.

- Kleinberg, J. M. (2000). Navigation in a small world. Nature, 406(6798), 845.

- Malkov, Y., Ponomarenko, A., Logvinov, A., & Krylov, V. (2014). Approximate nearest neighbor algorithm based on navigable small world graphs. Information Systems, 45, 61-68.

- Watts, D. J., & Strogatz, S. H. (1998). Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature, 393(6684), 440-442.

- Arya, S., & Mount, D. M. (1993). Approximate nearest neighbor queries in fixed dimensions. In Proceedings of the fourth annual ACM-SIAM symposium on Discrete algorithms (pp. 271-280).

- Wang, J., & Li, S. (2012). Query-driven iterated neighborhood graph search for large scale indexing. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM international conference on Multimedia (pp. 179-188).

- Jégou, H., Douze, M., & Schmid, C. (2011). Product quantization for nearest neighbor search. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 33(1), 117-128.

- Andoni, A., & Indyk, P. (2008). Near-optimal hashing algorithms for approximate nearest neighbor in high dimensions. Communications of the ACM, 51(1), 117-122.

- Bentley, J. L. (1975). Multidimensional binary search trees used for associative searching. Communications of the ACM, 18(9), 509-517.

- Lowe, D. G. (2004). Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. International Journal of Computer Vision, 60(2), 91-110.

- Pennington, J., Socher, R., & Manning, C. D. (2014). Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (pp. 1532-1543).

- Bolettieri, P., Esuli, A., Falchi, F., Lucchese, C., Perego, R., Piccioli, T., & Rabitti, F. (2009). CoPhIR: a test collection for content-based image retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:0905.4627.

- Boytsov, L., & Naidan, B. (2013). Engineering efficient and effective non-metric space library. In Similarity Search and Applications (pp. 280-293).

- Johnson, J., Douze, M., & Jégou, H. (2019). Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. IEEE Transactions on Big Data, 7(3), 535-547.

- Harwood, B., & Drummond, T. (2016). FANNG: Fast approximate nearest neighbour graphs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 5713-5722).

- Dong, W., Moses, C., & Li, K. (2011). Efficient k-nearest neighbor graph construction for generic similarity measures. In Proceedings of the 20th international conference on World wide web (pp. 577-586).

- Aumüller, M., Bernhardsson, E., & Faithfull, A. (2017). ANN-benchmarks: A benchmarking tool for approximate nearest neighbor algorithms. In International Conference on Similarity Search and Applications (pp. 34-49).

- Babenko, A., & Lempitsky, V. (2016). Efficient indexing of billion-scale datasets of deep descriptors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 2055-2063).

- LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y., & Haffner, P. (1998). Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE, 86(11), 2278-2324.

- Toussaint, G. T. (1980). The relative neighbourhood graph of a finite planar set. Pattern Recognition, 12(4), 261-268.

- Navarro, G. (2002). Searching in metric spaces by spatial approximation. The VLDB Journal, 11(1), 28-46.

Technical Articles and Blogs

- Hierarchical navigable small world - Wikipedia

- Hierarchical Navigable Small Worlds (HNSW) - Pinecone

- Introduction to HNSW: Hierarchical Navigable Small World - Analytics Vidhya

- What are Hierarchical Navigable Small Worlds (HNSW)? - DataStax

- Understanding Hierarchical Navigable Small Worlds (HNSW) - Zilliz

- What’s The Story With HNSW? - Towards Data Science

- Similarity Search, Part 4: Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) - Towards Data Science

- A Visual Guide to the Hierarchical Navigable Small World Algorithm