On test-time compute for language models

Recent advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) have highlighted the importance of scaling test time compute for enhanced reasoning capabilities and improved performance. This shift signifies a departure from the traditional focus on pre-training, where increasing data size and parameters were considered the primary drivers of model performance.

Traditionally, the dominant paradigm in LLM development was to scale the pre-training process, believing that larger models trained on more extensive datasets would automatically lead to better performance. This approach yielded impressive results, exemplified by the evolution of the GPT series, where each iteration demonstrated improved performance with increasing parameters and data size. However, this scaling approach has encountered limitations, primarily due to the escalating costs of building and maintaining the massive infrastructure required to train and operate such large models. Moreover, the availability of high-quality text data for training is finite and not growing at the pace required to sustain this scaling trend. Consequently, the returns on investment in terms of performance improvements have begun to diminish with increasing model size, leading to a plateau in the effectiveness of pre-training scaling.

The limitations of pre-training scaling have led to a paradigm shift towards exploring the potential of scaling test time compute. This approach involves allowing models to “think” longer during inference, enabling them to engage in more complex reasoning processes and refine their outputs. The rationale behind this shift is rooted in the observation that humans typically achieve better results when given more time and resources to deliberate on a problem. Applying this principle to LLMs, the focus has moved towards optimizing the inference stage, where models can leverage additional compute resources to improve their reasoning and problem-solving abilities.

Primary strategies have emerged for scaling test time compute

Enhancing Reasoning through Fine-tuning and Reinforcement Learning: This approach focuses on refining the inherent reasoning abilities of LLMs by fine-tuning them to generate more extensive chains of thought, mimicking the human process of breaking down complex problems into smaller, more manageable steps. Beyond simply mimicking the appearance of reasoning, reinforcement learning techniques are employed to instill actual reasoning behavior into the models. OpenAI’s o1 and o3 models exemplify this approach, showcasing the potential of reinforcement learning in enabling models to engage in complex reasoning tasks.

The “Score” paper published by Google DeepMind offers valuable insights into the implementation of reinforcement learning for instilling self-correction behavior in LLMs. This paper introduces a two-stage reinforcement learning process that goes beyond merely optimizing for accurate responses. Instead, it focuses on training the model to improve its responses iteratively. The first stage primes the model to learn from its initial response and generate a better second response. This sets the stage for the second stage, where a joint optimization of both responses takes place. The use of reward shaping in this stage prioritizes rewarding improvements between consecutive responses rather than just rewarding the final answer’s accuracy. This method effectively trains the model to develop self-correction as an inherent behavior, contributing to its ability to reason more effectively.

Leveraging Decoding Strategies and Generation-Based Search: This strategy focuses on expanding the exploration of potential solutions during the decoding phase, i.e., the process of generating output text from the model. Instead of relying on a single output from the model, these methods involve generating multiple candidate answers and then employing a separate verifier to identify the best solution.

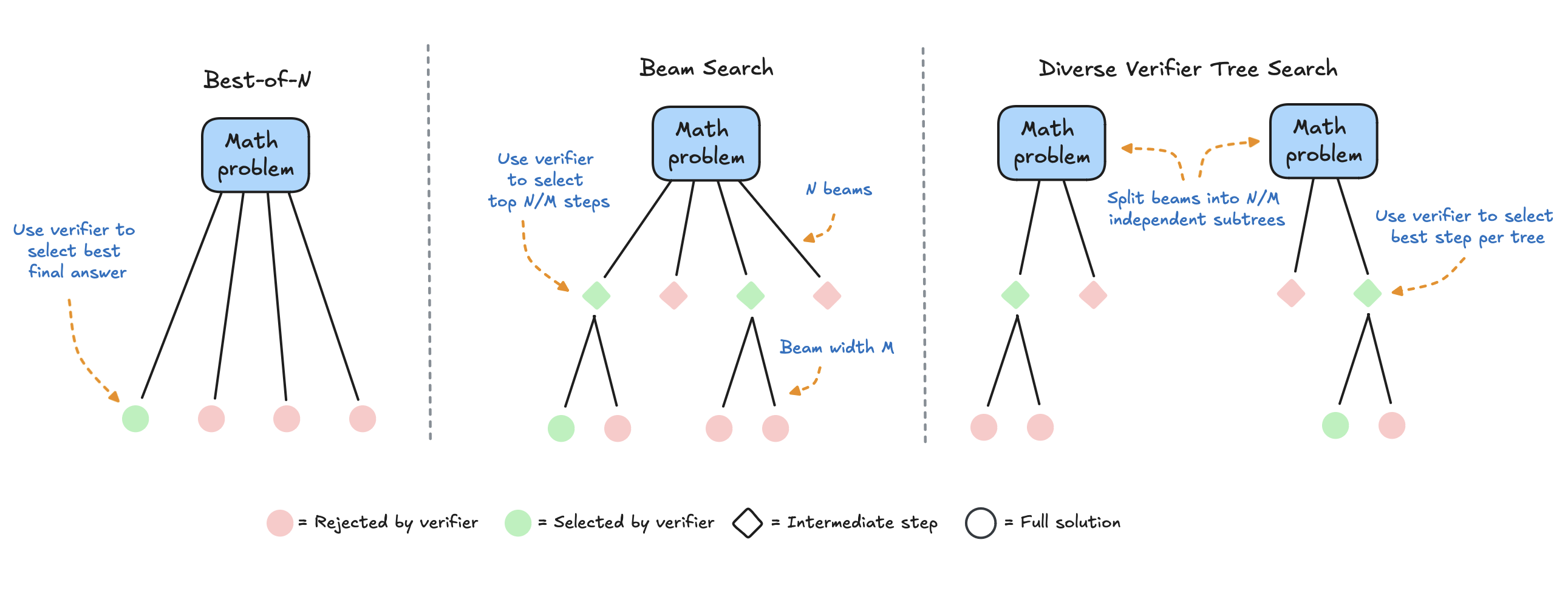

Hugging Face’s blog post “Scaling Test Time Compute with Open Models” presents three key search-based inference methods that fall under this category:

Best of N: This straightforward approach generates a predetermined number of independent responses to a given prompt and then selects the answer that receives the highest score from a reward model, indicating the most confident or potentially correct answer. A variation of this method, known as weighted best of N, aggregates the scores across all identical responses, giving more weight to answers that appear more frequently. This approach balances the confidence of the reward model with the frequency of occurrence, effectively prioritizing high-quality answers that are consistently generated.

Beam Search: This method delves deeper into the reasoning process by evaluating the individual steps involved in arriving at a solution. Instead of generating complete answers, the model generates a series of steps towards a solution. A process reward model then evaluates each step, assigning scores based on their correctness or relevance to the problem. Only the steps that receive scores above a certain threshold are retained, and the process continues by generating subsequent steps from these high-scoring points. This iterative process, guided by the process reward model, allows the search to navigate towards more promising solution paths, effectively pruning less likely or incorrect paths. This approach is particularly effective for complex reasoning tasks where breaking down the problem into smaller steps is crucial for arriving at the correct answer.

Diverse Verifier Tree Search (DVTS): This method addresses a potential limitation of beam search where the search may prematurely converge on a single path due to an exceptionally high reward at an early step, potentially overlooking other viable solution paths. DVTS mitigates this issue by introducing diversity into the search process. Instead of maintaining a single search tree, it splits the tree into multiple independent subtrees, allowing the exploration of diverse solution paths simultaneously. This ensures that the search does not get stuck in a single, potentially suboptimal path, promoting a more thorough exploration of the solution space. This method has shown promising results, particularly when dealing with higher compute budgets, where exploring a wider range of solutions becomes feasible.

The effectiveness of these scaling test time compute strategies has been demonstrated through evaluations using the Math 500 benchmark, a dataset specifically designed to assess the mathematical reasoning capabilities of LLMs. These evaluations have revealed that scaling test time compute can lead to significant improvements in accuracy, even when applied to smaller models. One notable finding is that applying the weighted best of N approach to a relatively small 1 billion parameter Llama model resulted in performance almost on par with an 8 billion parameter model, highlighting the potential of this technique to bridge the performance gap between smaller and larger models.

Furthermore, research has indicated that the optimal strategy for scaling test time compute is not one-size-fits-all but rather depends on factors like question difficulty and the available compute budget. Different strategies excel under different conditions. For instance, majority voting, the simplest approach of selecting the most frequently generated answer, has been found to perform surprisingly well on less difficult questions. However, as the complexity of the questions increases, more sophisticated methods like DVTS, which prioritize exploring a diverse set of solutions, begin to show superior performance. This suggests that an optimal approach to scaling test time compute involves dynamically selecting the most appropriate strategy based on the specific characteristics of the task and the computational resources available.

This dynamic approach to scaling test time compute has led to remarkable results, enabling smaller models to achieve performance levels comparable to, or even exceeding, those of significantly larger models. For example, by leveraging the optimal scaling strategy, a 3 billion parameter Llama model was able to outperform the baseline accuracy of a much larger 70 billion parameter model, demonstrating the potential of this approach to achieve high performance with more efficient resource allocation.

Several experiments further validated the effectiveness of scaling test time compute, even when applied to models that are not specifically optimized for complex reasoning tasks. By applying beam search to a small, suboptimal model, it successfully solved pre-algebra problems, despite the model’s lack of specific training for mathematical reasoning. These results highlight the potential of these techniques to enhance the reasoning capabilities of a wide range of LLMs, even those not initially designed for such tasks.

In conclusion, the shift towards scaling test time compute represents a significant paradigm shift in the development of LLMs. This approach has demonstrated its potential to unlock enhanced reasoning capabilities and improve performance across a spectrum of models, from smaller, more efficient models to large, complex models. The ability to dynamically adjust the scaling strategy based on question difficulty and compute budget further enhances the effectiveness of this approach, allowing for the optimal allocation of resources to achieve the best possible outcomes. As research in this area continues to advance, it is likely that we will witness further breakthroughs in LLM performance, driven by the innovative application of scaling test time compute strategies.

One potential avenue for further exploration is to investigate the application of these scaling test time compute techniques to tasks beyond mathematics and STEM fields. While the current focus has been on areas where verification of answers is relatively straightforward, extending these approaches to more open-ended domains. Exploring how to effectively define and utilize reward models in these less structured domains could unlock the potential of these techniques for a wider range of applications.